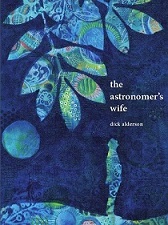

The Astronomer’s Wife.

Dick Alderson

Cottesloe, WA: Sunline Press. ISBN 9780980680263

RRP $20.

The Astronomer’s Wife by Dick Alderson is an assured and finely crafted first collection of poems. The writing is precise yet never bereft of detail, carefully constructed in terms of forms and line breaks, and employs some wonderfully quick and sly imagery. The author flits between kitchen tables, lemons, boyhood memories, moons and games of scrabble, all with a deft touch and real intimacy of voice. Alderson’s professional life as an engineer seems all too apparent in this distinctively written verse.

The real art of poetry, and indeed of any form of writing, is in the author’s creation of voice. In the case of a poetry collection, this means a different voice for each of the poems. The voice needs to be palpable, confident in terms of tone and delivery and, most importantly, consistent in its links between content an emotional implications. This final element creates the lift from page to reader. The Astronomer’s Wife contains some very fine examples of voicing. In ‘Lighthouse Hill’, we read

Yet there’s a grim intent:

even on those days the light

and the house stare the same way,

we have to imagine cliffs

and the light-keeper sleeping

or not sleeping

in that one-eyed room above the door

The use of ‘we’ as persona, as in many of the poems, gives the writing a universal and fable-like quality. But Alderson does not allow the poetry to become ponderous or sermon-like in tone. Instead, he often employs whimsy and the light-hearted or jocular ‘pull back’ from a scene or memory to create room for distance and perspective. In ‘Old Blue-Chin’ the last lines serve as a good example of this:

Someone’s had a piece of you,

knocked a dent

in your putty-head

and walked out of your life.

Let’s sit and commiserate

old Blue-Chin, old Moon.

Alderson’s imagery is often fleeting but always precise. He occasionally employs extended metaphor but prefers the furtive glance of words with the associated sudden rainbow of association and meaning. In ‘Almond Trees’, we read

My mother was the soft-shelled almond.

Her silver skin peeling back,

we would pick her every day

Here, and very often, the writing is rich in sensory detail. Alderson has a real affinity with the tactile and what it offers in terms of memory and mood. Another poem concerning childhood experiences, ‘Going to the Coast’, pulls the reader back to the car journey:

the car grinding up through the three gears,

sound as familiar to me

as my parents talking, the tones

and growl of words, part understood

And throughout the collection, the light-hearted use of simile, always accurate in perception and deceptively deep in terms of resonance. This from ‘Ibis’:

their long beaks, spiky feathers

fastidious but practical legs,

like old aunts doing a chore thoroughly

Alderson employs both line breaks and form in a thoughtful and subtle manner. He wisely allows the stanza breaks to work as silence, change of camera angle, shift of time perspective and moment of ponder. The use of ‘white space’ is perhaps one of the most powerful elements in the collection. ‘Forecast’ begins with the following two stanzas:

We have heard it of course

but the ants

tell it better

their queen has rheumatism

feels it

on her bones

The technique of starting wide and then tightening the focus is used quite frequently in this collection. The poem ‘Fall’, quoted below in its entirety, is a wonderful example of the many well-crafted poems with its sharp diction, subtle imagery and well planed denouement:

It clatters down

brown hand

curved and buckled

longest finger sticking

skew

cracked alien veins

and skinniest of arms

end in a burnt

desocketed elbow

a leaf

quite unlike

the poem I had thought

to write

There is much to like in this collection and many reasons to recommend it as a volume of very accessible and thoughtful prose. The poetry leaves the reader with a sense of wonder, a kindling of a primary curiosity in our surrounds and what they contain and promise.