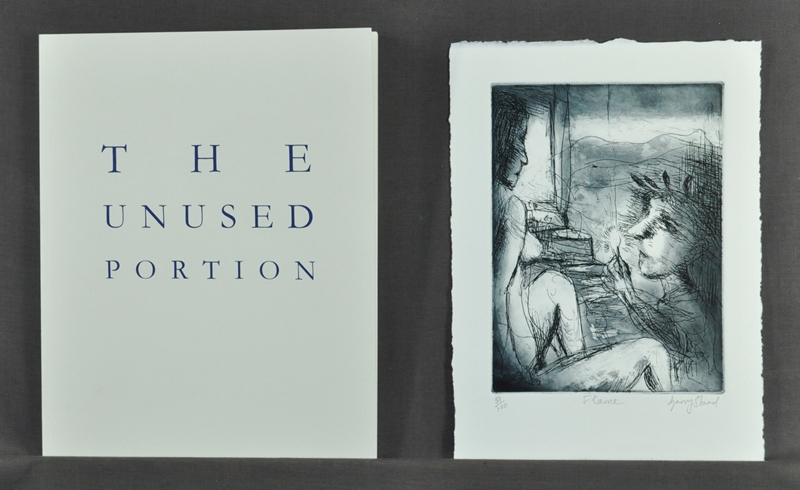

Lyn Hard, and Gary Shead (illustrations).

ISBN 1 875892 39 7. Sydney: ETT (Editions Tom Thompson), 2013. An edition of 100, with 50 copies signed by the poet and the artist.

RRP $30.

This is a handsome, elegant book, containing some longer, darker, slower poems than in Hard’s previous books. The high quality of the book’s luxurious, creamy paper (120gsm Conqueror cxu laid) adds to the pleasure of reading. The imagery of the poems is nothing less than wonderfully original. There is a controlled tenderness, quite the opposite of sentimentality.

This is sophisticated poetry, often witty and droll, with a vague wisp of melancholy that is very attractive. These are the poems of a man who has learnt what is what, what matters when leading to final things and who despises the shallow. For originality, try this (from ‘Barbados, dedicated to Charles Christopher Parker, Jr. 29/8/20 – 12/3/55’):

Warm Barbados:

the slow surf piles on the beach like blue pullovers being folded away

and the lost umbrellas of palms

accept the breeze

and their own raggedness...

The above comes from a section of the book comprising six poems based on jazz standards, written to be performed with a jazz group the same way a jazz musician plays a solo. Hard said to me recently, ‘I always thought I wasn’t influenced by other people but now I can see I was’.

For controlled tenderness, try this (from ‘A Song for My Father’):

You never met my father

if you think a song with a latin beat

is appropriate.

I’ve seen my father dance:

nothing moves below the waist,

not even the feet.

When he’s sober

It’s like a dashboard figure

sliding with the turns:

when he’s drunk

he bends and raises at the waist

like one of those oil pumps he used to work on,

but without as much rhythm

…

Last year my father told me, in conversation,

that his sight, hearing and hair were going

and that, evidently, his heart had finally done what he never could:

produce a latin beat

and I was the only one afraid.

Gary Shead’s drawings throughout the book sometimes match the poems in playfulness, whimsy and erotic tenderness. They are reminiscent of Chagall in their rather joyful innocence. (It takes a clever, experienced artist to make work that seems innocent.) The drawing ‘Lucifer’ refers straight-out to Goya.

The poem ‘Washing Up After the Last Supper’, written in the voice of the kitchen hand or owner, perhaps, slowly draws the picture of Christ and the disciples:

I was run off my feet

so I didn’t hear much of what was said

but it looked like a goodbye party to me

… …

(Can’t think of his name to save me but I know the family. His old man’s a cabinetmaker in Nazareth and his mom’s the ultimate Jewish mother. The boy has been a major trial for them.)

I think he was going away but where’s he going to?

That little donkey’s not gonna get him far.

As you see, often in the poems, there is a phantom chuckle.

There is an easy erudition in the poems about jazz composers, paintings and of famous artists (Van Gogh, Utrillo), places Vezelay, Compostella and biblical references. The effect of the poems is like lunching with a well dressed, well read, intelligent and amused friend who, though reluctant to show his feelings, reveals them slowly but aslant, with humour.

The conversation is full of art, jazz, friends, novels and poetry. Then, when we are half lit, an artist, a friend of the poet arrives, also merry. He joins us. And we go on. When I leave, my hat is askew. As with this book, altogether a rare pleasure.